Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

I get a lot of pleasure in bringing up a topical issue and then contributing nothing.

Today's News:

Hovertext:

I get a lot of pleasure in bringing up a topical issue and then contributing nothing.

I am a 42-year-old St. Louis native, a queer woman, and politically to the left of Bernie Sanders. My worldview has deeply shaped my career. I have spent my professional life providing counseling to vulnerable populations: children in foster care, sexual minorities, the poor.

For almost four years, I worked at The Washington University School of Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases with teens and young adults who were HIV positive. Many of them were trans or otherwise gender nonconforming, and I could relate: Through childhood and adolescence, I did a lot of gender questioning myself. I’m now married to a transman, and together we are raising my two biological children from a previous marriage and three foster children we hope to adopt.

All that led me to a job in 2018 as a case manager at The Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children's Hospital, which had been established a year earlier.

The center’s working assumption was that the earlier you treat kids with gender dysphoria, the more anguish you can prevent later on. This premise was shared by the center’s doctors and therapists. Given their expertise, I assumed that abundant evidence backed this consensus.

During the four years I worked at the clinic as a case manager—I was responsible for patient intake and oversight—around a thousand distressed young people came through our doors. The majority of them received hormone prescriptions that can have life-altering consequences—including sterility.

I left the clinic in November of last year because I could no longer participate in what was happening there. By the time I departed, I was certain that the way the American medical system is treating these patients is the opposite of the promise we make to “do no harm.” Instead, we are permanently harming the vulnerable patients in our care.

Today I am speaking out. I am doing so knowing how toxic the public conversation is around this highly contentious issue—and the ways that my testimony might be misused. I am doing so knowing that I am putting myself at serious personal and professional risk.

Almost everyone in my life advised me to keep my head down. But I cannot in good conscience do so. Because what is happening to scores of children is far more important than my comfort. And what is happening to them is morally and medically appalling.

The Floodgates Open

Soon after my arrival at the Transgender Center, I was struck by the lack of formal protocols for treatment. The center’s physician co-directors were essentially the sole authority.

At first, the patient population was tipped toward what used to be the “traditional” instance of a child with gender dysphoria: a boy, often quite young, who wanted to present as—who wanted to be—a girl.

Until 2015 or so, a very small number of these boys comprised the population of pediatric gender dysphoria cases. Then, across the Western world, there began to be a dramatic increase in a new population: Teenage girls, many with no previous history of gender distress, suddenly declared they were transgender and demanded immediate treatment with testosterone.

I certainly saw this at the center. One of my jobs was to do intake for new patients and their families. When I started there were probably 10 such calls a month. When I left there were 50, and about 70 percent of the new patients were girls. Sometimes clusters of girls arrived from the same high school.

This concerned me, but didn’t feel I was in the position to sound some kind of alarm back then. There was a team of about eight of us, and only one other person brought up the kinds of questions I had. Anyone who raised doubts ran the risk of being called a transphobe.

The girls who came to us had many comorbidities: depression, anxiety, ADHD, eating disorders, obesity. Many were diagnosed with autism, or had autism-like symptoms. A report last year on a British pediatric transgender center found that about one-third of the patients referred there were on the autism spectrum.

Frequently, our patients declared they had disorders that no one believed they had. We had patients who said they had Tourette syndrome (but they didn’t); that they had tic disorders (but they didn’t); that they had multiple personalities (but they didn’t).

The doctors privately recognized these false self-diagnoses as a manifestation of social contagion. They even acknowledged that suicide has an element of social contagion. But when I said the clusters of girls streaming into our service looked as if their gender issues might be a manifestation of social contagion, the doctors said gender identity reflected something innate.

To begin transitioning, the girls needed a letter of support from a therapist—usually one we recommended—who they had to see only once or twice for the green light. To make it more efficient for the therapists, we offered them a template for how to write a letter in support of transition. The next stop was a single visit to the endocrinologist for a testosterone prescription.

That’s all it took.

When a female takes testosterone, the profound and permanent effects of the hormone can be seen in a matter of months. Voices drop, beards sprout, body fat is redistributed. Sexual interest explodes, aggression increases, and mood can be unpredictable. Our patients were told about some side effects, including sterility. But after working at the center, I came to believe that teenagers are simply not capable of fully grasping what it means to make the decision to become infertile while still a minor.

Side Effects

Many encounters with patients emphasized to me how little these young people understood the profound impacts changing gender would have on their bodies and minds. But the center downplayed the negative consequences, and emphasized the need for transition. As the center’s website said, “Left untreated, gender dysphoria has any number of consequences, from self-harm to suicide. But when you take away the gender dysphoria by allowing a child to be who he or she is, we’re noticing that goes away. The studies we have show these kids often wind up functioning psychosocially as well as or better than their peers.”

There are no reliable studies showing this. Indeed, the experiences of many of the center’s patients prove how false these assertions are.

Here’s an example. On Friday, May 1, 2020, a colleague emailed me about a 15-year-old male patient: “Oh dear. I am concerned that [the patient] does not understand what Bicalutamide does.” I responded: “I don’t think that we start anything honestly right now.”

Bicalutamide is a medication used to treat metastatic prostate cancer, and one of its side effects is that it feminizes the bodies of men who take it, including the appearance of breasts. The center prescribed this cancer drug as a puberty blocker and feminizing agent for boys. As with most cancer drugs, bicalutamide has a long list of side effects, and this patient experienced one of them: liver toxicity. He was sent to another unit of the hospital for evaluation and immediately taken off the drug. Afterward, his mother sent an electronic message to the Transgender Center saying that we were lucky her family was not the type to sue.

How little patients understood what they were getting into was illustrated by a call we received at the center in 2020 from a 17-year-old biological female patient who was on testosterone. She said she was bleeding from the vagina. In less than an hour she had soaked through an extra heavy pad, her jeans, and a towel she had wrapped around her waist. The nurse at the center told her to go to the emergency room right away.

We found out later this girl had had intercourse, and because testosterone thins the vaginal tissues, her vaginal canal had ripped open. She had to be sedated and given surgery to repair the damage. She wasn’t the only vaginal laceration case we heard about.

Other girls were disturbed by the effects of testosterone on their clitoris, which enlarges and grows into what looks like a microphallus, or a tiny penis. I counseled one patient whose enlarged clitoris now extended below her vulva, and it chafed and rubbed painfully in her jeans. I advised her to get the kind of compression undergarments worn by biological men who dress to pass as female. At the end of the call I thought to myself, “Wow, we hurt this kid.”

There are rare conditions in which babies are born with atypical genitalia—cases that call for sophisticated care and compassion. But clinics like the one where I worked are creating a whole cohort of kids with atypical genitals—and most of these teens haven’t even had sex yet. They had no idea who they were going to be as adults. Yet all it took for them to permanently transform themselves was one or two short conversations with a therapist.

Being put on powerful doses of testosterone or estrogen—enough to try to trick your body into mimicking the opposite sex—-affects the rest of the body. I doubt that any parent who's ever consented to give their kid testosterone (a lifelong treatment) knows that they’re also possibly signing their kid up for blood pressure medication, cholesterol medication, and perhaps sleep apnea and diabetes.

But sometimes the parents’ understanding of what they had agreed to do to their children came forcefully:

Neglected and Mentally Ill Patients

Besides teenage girls, another new group was referred to us: young people from the inpatient psychiatric unit, or the emergency department, of St. Louis Children’s Hospital. The mental health of these kids was deeply concerning—there were diagnoses like schizophrenia, PTSD, bipolar disorder, and more. Often they were already on a fistful of pharmaceuticals.

This was tragic, but unsurprising given the profound trauma some had been through. Yet no matter how much suffering or pain a child had endured, or how little treatment and love they had received, our doctors viewed gender transition—even with all the expense and hardship it entailed—as the solution.

Some weeks it felt as though almost our entire caseload was nothing but disturbed young people.

For example, one teenager came to us in the summer of 2022 when he was 17 years old and living in a lockdown facility because he had been sexually abusing dogs. He’d had an awful childhood: His mother was a drug addict, his father was imprisoned, and he grew up in foster care. Whatever treatment he may have been getting, it wasn’t working.

During our intake I learned from another caseworker that when he got out, he planned to reoffend because he believed the dogs had willingly submitted.

Somewhere along the way, he expressed a desire to become female, so he ended up being seen at our center. From there, he went to a psychologist at the hospital who was known to approve virtually everyone seeking transition. Then our doctor recommended feminizing hormones. At the time, I wondered if this was being done as a form of chemical castration.

That same thought came up again with another case. This one was in spring of 2022 and concerned a young man who had intense obsessive-compulsive disorder that manifested as a desire to cut off his penis after he masturbated. This patient expressed no gender dysphoria, but he got hormones, too. I asked the doctor what protocol he was following, but I never got a straight answer.

In Loco Parentis

Another disturbing aspect of the center was its lack of regard for the rights of parents—and the extent to which doctors saw themselves as more informed decision-makers over the fate of these children.

In Missouri, only one parent’s consent is required for treatment of their child. But when there was a dispute between the parents, it seemed the center always took the side of the affirming parent.

My concerns about this approach to dissenting parents grew in 2019 when one of our doctors actually testified in a custody hearing against a father who opposed a mother’s wish to start their 11-year-old daughter on puberty blockers.

I had done the original intake call, and I found the mother quite disturbing. She and the father were getting divorced, and the mother described the daughter as “kind of a tomboy.” So now the mother was convinced her child was trans. But when I asked if her daughter had adopted a boy’s name, if she was distressed about her body, if she was saying she felt like a boy, the mother said no. I explained the girl just didn’t meet the criteria for an evaluation.

Then a month later, the mother called back and said her daughter now used a boy’s name, was in distress over her body, and wanted to transition. This time the mom and daughter were given an appointment. Our providers decided the girl was trans and prescribed a puberty blocker to prevent her normal development.

The father adamantly disagreed, said this was all coming from the mother, and a custody battle ensued. After the hearing where our doctor testified in favor of transition, the judge sided with the mother.

‘I Want My Breasts Back’

Because I was the main intake person, I had the broadest perspective on our existing and prospective patients. In 2019, a new group of people appeared on my radar: desisters and detransitioners. Desisters choose not to go through with a transition. Detransitioners are transgender people who decide to return to their birth gender.

The one colleague with whom I was able to share my concerns agreed with me that we should be tracking desistance and detransition. We thought the doctors would want to collect and understand this data in order to figure out what they had missed.

We were wrong. One doctor wondered aloud why he would spend time on someone who was no longer his patient.

But we created a document anyway and called it the Red Flag list. It was an Excel spreadsheet that tracked the kind of patients that kept my colleague and me up at night.

One of the saddest cases of detransition I witnessed was a teenage girl, who, like so many of our patients, came from an unstable family, was in an uncertain living situation, and had a history of drug use. The overwhelming majority of our patients are white, but this girl was black. She was put on hormones at the center when she was around 16. When she was 18, she went in for a double mastectomy, what’s known as “top surgery.”

Three months later she called the surgeon’s office to say she was going back to her birth name and that her pronouns were “she” and “her.” Heartbreakingly, she told the nurse, “I want my breasts back.” The surgeon’s office contacted our office because they didn’t know what to say to this girl.

My colleague and I said that we would reach out. It took a while to track her down, and when we did we made sure that she was in decent mental health, that she was not actively suicidal, that she was not using substances. The last I heard, she was pregnant. Of course, she’ll never be able to breastfeed her child.

‘Get On Board, Or Get Out’

My concerns about what was going on at the center started to overtake my life. By spring 2020, I felt a medical and moral obligation to do something. So I spoke up in the office, and sent plenty of emails.

Here’s just one example: On January 6, 2022, I received an email from a staff therapist asking me for help with a case of a 16-year-old transgender male living in another state. “Parents are open to having patient see a therapist but are not supportive of gender and patient does not want parents to be aware of gender identity. I am having a challenging time finding a gender affirming therapist.”

I replied:

“I do not ethically agree with linking a minor patient to a therapist who would be gender affirming with gender as a focus of their work without that being discussed with the parents and the parent agreeing to that kind of care.”

In all my years at the Washington University School of Medicine, I had received solidly positive performance reviews. But in 2021, that changed. I got a below-average mark for my “Judgment” and “Working Relationships/Cooperative Spirit.” Although I was described as “responsible, conscientious, hard-working and productive” the evaluation also noted: “At times Jamie responds poorly to direction from management with defensiveness and hostility.”

Things came to a head at a half-day retreat in summer of 2022. In front of the team, the doctors said that my colleague and I had to stop questioning the “medicine and the science” as well as their authority. Then an administrator told us we had to “Get on board, or get out.” It became clear that the purpose of the retreat was to deliver these messages to us.

The Washington University system provides a generous college tuition payment program for long-standing employees. I live by my paycheck and have no money to put aside for five college tuitions for my kids. I had to keep my job. I also feel a lot of loyalty to Washington University.

But I decided then and there that I had to get out of the Transgender Center, and to do so, I had to keep my head down and improve my next performance review.

I managed to get a decent evaluation, and I landed a job conducting research in another part of The Washington University School of Medicine. I gave my notice and left the Transgender Center in November of 2022.

What I Want to See Happen

For a couple of weeks, I tried to put everything behind me and settled into my new job as a clinical research coordinator, managing studies regarding children undergoing bone marrow transplants.

Then I came across comments from Dr. Rachel Levine, a transgender woman who is a high official at the federal Department of Health and Human Services. The article read: “Levine, the U.S. assistant secretary for health, said that clinics are proceeding carefully and that no American children are receiving drugs or hormones for gender dysphoria who shouldn’t.”

I felt stunned and sickened. It wasn’t true. And I know that from deep first-hand experience.

So I started writing down everything I could about my experience at the Transgender Center. Two weeks ago, I brought my concerns and documents to the attention of Missouri’s attorney general. He is a Republican. I am a progressive. But the safety of children should not be a matter for our culture wars.

Click here to read Jamie Reed’s letter to the Missouri AG.

Given the secrecy and lack of rigorous standards that characterize youth gender transition across the country, I believe that to ensure the safety of American children, we need a moratorium on the hormonal and surgical treatment of young people with gender dysphoria.

In the past 15 years, according to Reuters, the U.S. has gone from having no pediatric gender clinics to more than 100. A thorough analysis should be undertaken to find out what has been done to their patients and why—and what the long-term consequences are.

There is a clear path for us to follow. Just last year England shut down the Tavistock Centre, the only youth gender clinic in the country, after an investigation revealed shoddy practices and poor patient treatment. Sweden and Finland, too, have investigated pediatric transition and greatly curbed the practice, finding there is insufficient evidence of help, and danger of great harm.

Some critics describe the kind of treatment offered at places like the Transgender Center where I worked as a kind of national experiment. But that’s wrong.

Experiments are supposed to be carefully designed. Hypotheses are supposed to be tested ethically. The doctors I worked alongside at the Transgender Center said frequently about the treatment of our patients: “We are building the plane while we are flying it.” No one should be a passenger on that kind of aircraft.

Tonight at 6:00 p.m. PST we are hosting a conversation with Jamie Reed. To join us (event details will be sent later today) become a subscriber now:

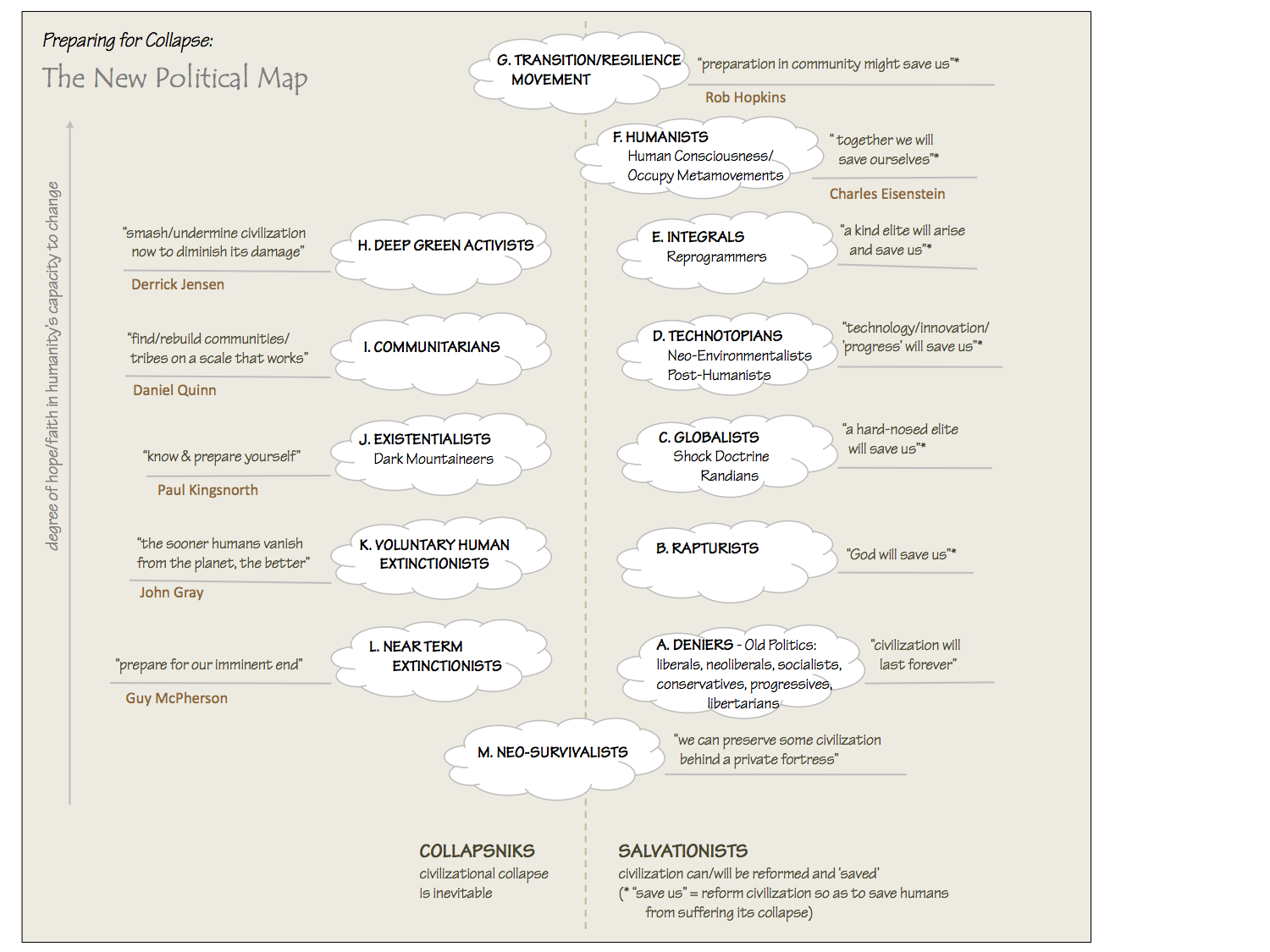

my now-slightly-outdated map of worldviews about collapse; right-click and open in a new tab to see it full-sized

It’s interesting to listen to social philosopher Daniel Schmachtenberger try to reconcile his assessment of the state of the world with his vehement insistence that we have to try as hard we possibly can to avert the ‘metacrisis’ that threatens to bring about the collapse of human civilization and the extinction of most or all life on earth, including humans.

In a recent video, he said:

How can evolutionarily nasty chimpanzees with a high orientation for conflict and irrationality, with nuclear weapons and AI and synthetic biology, with a history of using technology in conflict-oriented and harm-externalizing ways, how can 8 billion of us with exponential tech [increasingly available to all] do a good job of governing that much power? It doesn’t actually look that promising.

Yet he insists that “we cannot know for certain” that we are fucked (or that we are not), so we each have a responsibility to do what we can, working with others, to pull us back from the brink.

His argument reveals a curious quirk about humans and our relationship to complexity, uncertainty, and hope. We seem completely preoccupied with what John Gray calls “the needs of the moment”, and it is clear that this preoccupation has directly produced the metacrisis (a combination of many, unintended, crises and system collapses — economic, ecological, political, social, health, educational, resource, technological, and, for some, spiritual/religious) in which we find ourselves. Yet we continue to cling to hope for our future when all logic says it’s unfounded.

Daniel harks back to when he was 12-15 years old, and first became aware of the monstrous cruelty to animals inherent in factory farming. (This is also how my own political activism started, though I was a bit older.) It seemed an impossibly complex problem to solve. But for Daniel, as long as there was some uncertainty about the outcome, some small possibility of an unknown occurrence (lab-produced animal-less meat?) that could unexpectedly intervene in the system and radically alter its trajectory, he could not allow that it was ever acceptable to give up, to shrug and say “There’s nothing we can do.”

Of course Daniel is enormously biologically, economically and culturally privileged, and it would be easy to say “Daniel, that’s easy for you to say…”. But while he acknowledges his enormous privilege, Daniel insists he is not exceptional or unusual, and that our inherent biophilia, instincts and basic human capacities make it possible, and essential, for everyone to play a role in understanding and working fiercely to resolve the metacrisis in the best way possible.

My philosophy of late has been that we have no free will, and that our beliefs and behaviours are entirely conditioned, such that “we’re all doing our best”. I think Daniel is saying “we can and will and must do better”.

I think he’s wrong about the capacities of the human species, though I do accept that if everyone in the world was as intelligent, as informed, as thoughtful, as open-minded, as engaged, as curious, as connected, as humble, as articulate, and as coherent in their thinking as he is, we really might be able to ‘save the world’ from what we have unintentionally wrought.

Instead, we are where we are. I don’t believe we can blame humans for being preoccupied with “the needs of the moment” and for only being able to do their inadequate-to-the-current-situation best.

Here’s a thought experiment to illustrate why I think this is so:

Suppose you knew, or believed, the following:

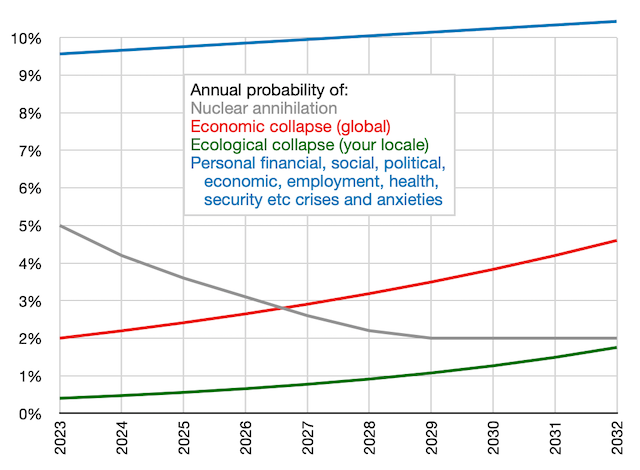

I’m not asking you to accept these numbers as true — obviously we cannot know with any precision what is going to happen and when. But let’s assume you buy these probabilities. Your near-term perspective, now in 2023, of the existential risks you face would then be as illustrated below:

What demands the most of your attention, and perhaps keeps you awake at night, would naturally be the personal needs of the moment, shown in blue. If you have any bandwidth left for existential anxiety and are paying any attention to the doomscroll, your remaining preoccupation would likely be the risk of nuclear war, as its probability has soared over the past year. The horrific, longer-term economic and ecological (and other) crises we face would understandably be pushed to the back of your mind.

There’s nothing wrong-headed or inappropriately selfish about that. We have survived because our conditioning has inclined us to focus on the personal and the short-term.

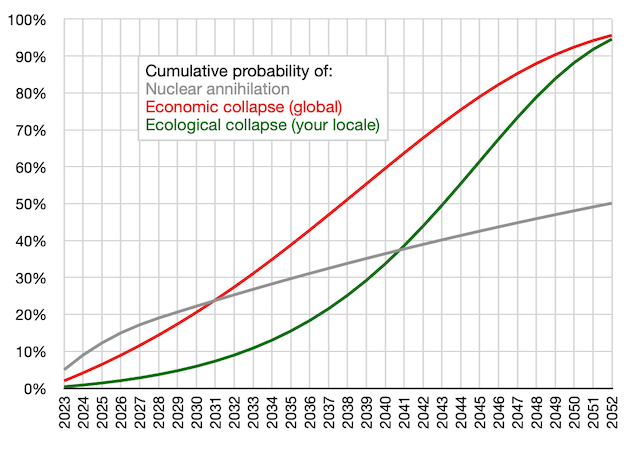

But what if we extended the chart above over a longer-term risk horizon, and looked at the cumulative risks of these elements of the metacrisis, rather than the annual risks? Of course, the further out we go, the greater the uncertainty and the likelihood of our guess being wrong. But this is what it might look like, using the same hypothetical assumptions above:

“It doesn’t look promising!”

This chart suggests a different focus for how we view and prioritize the crises we are facing. This way of looking at them makes a lot of sense, logically and statistically, but this is not how humans make sense of things. For a start, the longer out we go, the more we are inclined to discount our belief in the likelihood of these crises happening, because of their enormous uncertainty*. Secondly, we know that such predictions are prone to being rendered unreliable and useless by “black swan” events (like pandemics), by novel technologies, and by other unforeseeable developments (like cosmic radiation, asteroids, and solar flares). And third, we don’t think in terms of cumulative risk; like lousy casino players, we only see one roll ahead, and if we dodge a bullet, we think the likelihood of dodging the next one is suddenly much higher.

So if we make it to 2032 (a toss-up), or 2039 (unlikely) with none of these crises having occurred, we are probably going to be unduly optimistic that they won’t happen in the next decade or two either (just as the Davos gnomes were ridiculously optimistic in late 2019 that there would be no pandemic, because there hadn’t been one recently). Same logic for the “big one” destroying Cascadia.

And when/if our systems are still basically functional in the 2030s, it’s likely our focus will still be the short-term challenges we face over the next year or two, which means we will remain preoccupied with our personal needs of the moment, until global economic or local ecological collapse changes everything.

That is one reason we will not address the metacrisis until it is too late. There is another, very human reason, and that is that we can’t, and don’t want to try to, fathom the enormous complexity and interrelatedness of the elements of the metacrisis, each one of which is enormously complex in itself. For most, it’s enough to make our heads explode. We believe it to be impossible to understand and deal with, so it in fact becomes impossible to understand and deal with. This is what “doing our best” means for human animals. And that is not a criticism.

Yet despite this, we hope. As my map of the different types of Salvationists at the top of this post describes, hope comes in lots of flavours: Hope that the gods or aliens will take care of us. Hope that technology and innovation will come to the rescue. Hope that some human elite of leaders, beneficent or hard-nosed, will save us from ourselves. Hope that a massive spontaneous return to self-sufficient community-based living or global uplifting of human consciousness will solve the crisis. Place your bets and spin the wheel.

And then there are deniers who hope and believe that it’s all a hoax. And there are the NTHE Gaia-lovers who hope our awful species will perish quickly so the planet can start to recover from the human experiment sooner rather than later.

What is behind this hope? What is it about our perverse species that uniquely chooses to believe things, and do things, based purely on this thing called hope? Is it some kind of mental illness endemic to humans?

What causes us to elect a president who runs a campaign based solely on hope — twice? What causes abused spouses and children to stay around in the hope the abuser is going to change? What causes people to desperately keep loved-ones on life support, when the prognosis is dismal? Why does Hollywood, playing to the crowd, show success at CPR at a rate ten times higher than its real-life success rate? Why do so many believe that the only alternative to unwarranted hope is crippling despair?

I have said, ad nauseam, that we believe what we want to believe, and the truth be damned. So it must follow that hope is what we want to believe is true, and want to believe will happen, even when we think that belief is fraught with risk. Hope is future-oriented, and there is evidence that we are the only species on the planet that is so oriented. What is underlying that hopeful belief? Is it shame or guilt about what we have done wrong or failed to do successfully (like leave a healthy planet for our children) up ’til now? Is it anger about past ‘wrongs’ we want and hope to see atoned? Is it fear of a future we can’t bear to face, so we mask it with hopefulness?

I have, for now, come to grips with a realization that we seem to have no free will or control over our actions and inactions. When I acknowledged that everything we do is conditioned, I was able to give up hope. We can’t know or control what the future will bring, so what will happen is the only thing that could have happened. If we are hopeful on that basis, we are almost sure to be disappointed. But when we are disappointed, we may just double-down and hope even more fervently that things will be better next time, or next year. We are hope junkies.

Caitlin Johnstone just wrote a very eloquent, lovely. heartfelt essay about hope and wonder. On hope, in remarkably Schmachtenberger-ish language, she writes:

Hopelessness, when it comes to the fate of humanity, is an irrational position. The belief that we’re all inevitably going to destroy ourselves or keep marching into the depths of dystopia to the beat of the propaganda drum assumes a level of knowledge that nobody can possibly have. Nobody could possibly have enough information to draw that conclusion with any degree of confidence, and believing that you have is actually a bit arrogant. You don’t know what the future holds for our species, what unpredictable sociological, technological, environmental or situational surprises lie in wait that could cause a radical deviation from the norm… Hopelessness is the baseless and irrational shrinking of possibilities down to the spectrum of what’s known.

Yes, we cannot know, but lots of research shows that the people who have studied and learned the most about history and human nature and the current state of the world and how it works, are the most pessimistic about the future — the least hopeful. I’ve talked to enough climate scientists to think this is probably true.

And yes, we cannot know enough to be sure of the endgame, or even if there will be one. But, on the balance of probabilities, we can get a pretty strong sense that “it doesn’t look promising”. Why, then, can’t we seem to manage to move beyond hope, and just accept what is, and how fascinating the human experiment has been, despite its discouraging trajectory?

In her essay Caitlin moves on, deliciously, from hope to wonder:

If you really open your eyes, you’ll notice that the world is crackling with so much radiant beauty and wonder that even if we were to lose it all tomorrow, it would have been enough. A lucid perception of reality brings with it an experience of awe, and an on-your-knees gratitude for the fact that there was ever anything at all. From a perspective that isn’t clouded with mental narrative and internal distraction, each moment is too miraculous and too priceless a gift to get hung up on the possibility that it might not last.

Wonder is always accessible, even in the depths of sadness or depression. You might not always be able to find it in the trees or the butterflies, but you can always find it somewhere, often in the sadness itself. Even in the pain and despondency. Even in the car exhaust and the tattered billboards. Even in the background shimmering of existence. It’s always there to be found; you just might have to zoom out or zoom in your camera in order to find your access point to it.

Yes, and yes, there is wonder! The joyful pessimist in me finds it everywhere. The eight billion of us comprise only 7% of the over 100 billion humans who have ever lived on this planet. We are among the blessed 7% who will possibly get to witness the final chapter of the human experiment, who get to know how the story ends! And if it ends badly, well, that’s the only way it could have ended. All civilizations, and all stories, end. We all did our best. Nothing to be sad or ashamed about.

It doesn’t have to have a happy ending to be a wonderful story.

So, on the balance of probabilities, it’s more-or-less hopeless. And that’s fine, because we don’t need to be hopeful. Other creatures have lived for millions or billions of years without the need for hope. They understand this, in a way our species, smart and destructive and reckless and whiny as a young child in a family of patient, wise elders, is still far from learning.

If they have a purpose, it has nothing to do with hope, and everything to do with wonder. We might learn this, if we last long enough.

But I’m not hopeful.

* At the other extreme, there is an emotionally unmoored but very well-financed fringe group, including Elon Musk, who subscribe to a belief called Longtermism, that advocates actions, even if they could entail massive death and suffering of the planet’s current inhabitants, if those actions increased the odds of even more humans being alive in the far distant future. (Uncertainty is not factored in to their ghastly calculus.)

Dog Bows to Bible - What this little dog did to the holy book of God will knock your shit out of your ass hole.

Prince Andrew must be heartbroken. Sounds of sobbing like a little girl were reported from his chambers.

Goons_TXT

on Friday, September 9th, 2022 1:24am

Goons_TXT

on Friday, September 9th, 2022 1:24am